The team at Disney Research has been working on the Tesla Touch prototype for almost a year. Tesla Touch is a touchscreen feedback technology that relies on the principles of electrovibration to simulate textures on a user’s fingertips. This article expands on the overview of the technology I wrote earlier, and it is based on a recent demonstration meeting at CES that I had with Ivan Poupyrev and Ali Israr, members of the Tesla Touch development team.

The first thing to note is that the Tesla Touch is a prototype; it is not a productized technology just yet. As with any promising technology, there are a number of companies working with the Tesla Touch team to figure out how they might integrate the technology into their upcoming designs. The concept behind the Tesla Touch is based on technology that researchers in the 1950’s were working on to assist blind people. The research fell dormant and the Tesla Touch team has revived it. The technology shows a lot of interesting promise, but I suspect the process of making it robust enough for production designs will uncover a number of use-case challenges (like it probably did for the original research team).

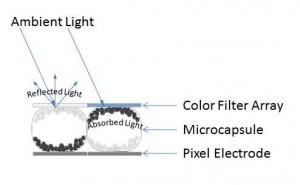

The Tesla Touch controller modulates a periodic electrostatic charge across the touch surface which attracts and repels the electrons in the user’s fingertip towards or away from the touch surface – in effect, varying the friction the user experiences while moving their finger across the surface. Ali has been characterizing the psychophysics of the technology over the last year to understand how people perceive tactile sensations of the varying electrostatic field. Based on my experience with sound bars last week (which I will write about in another article), I suspect the controller for this technology will need to be able to manage a number of usage profiles to accommodate different operating conditions as well as differences between how users perceive the signal it produces.

Ali shared that the threshold to feel the signal was an 8V peak-to-peak modulation; however, the voltage swing on the prototype ranged from 60 to 100 V. The 80 to 100 V signal felt like a comfortable tug on my finger; the 60 to 80 V signal presented a much lighter sensation.Because our meeting was more than a quick demonstration in a booth, I was able to uncover one of the use-case challenges. When I held the unit in my hand, the touch feedback worked great; however, if I left the unit on the table and touched it with only one hand, the touch feedback was nonexistent. This was in part because the prototype is based on the user providing the ground for the system. Ivan mentioned that the technology can work without the user grounding it, but that it requires the system to use larger voltage swings.

In order for the user to feel the feedback, their finger must be in motion. This is consistent with how people experience touch, so there is no disconnect between expectations and what the system can deliver. The expectation that the user will more easily sense the varying friction with lateral movement of their finger is also consistent with observations that the team at Immersion, a mechanical-based haptics company, shared with me when simulating touch feedback on large panels with small motors or piezoelectric strips.

The technology prototype used a capacitive touch screen – demonstrating that the touch sensing and the touch feedback systems can work together. The prototype was modulating the charge on the touch surface at up to a 500 Hz rate which is noticeably higher than the 70Hz rate of the its touch sensor. A use-case challenge for this technology is that it requires a conductive material or substance at the touch surface in order to convey texture feedback to the user. While a 100 V swing is sufficient for a user to sense feedback with their finger, it might not be large enough of a swing to sense it through an optimal stylus. Using gloves will also impair or prevent the user from sensing the feedback.

A fun surprise occurred during one of the demonstration textures. In this case, the display showed a drinking glass. When I rubbed the display away from the drinking glass, the surface was a normal smooth surface. When I rubbed over the surface that showed the drinking glass, I felt a resistance that met my expectation for the glass. I then decided to rub repeated over that area to see if the texture would change and was rewarded with a sound similar to rubbing/cleaning a drinking glass with your finger. Mind you, the sound did not occur when I rubbed the other parts of the display.

The technology is capable of conveying coarse texture transitions, such as from a smooth surface to a rough or heavy surface. It is able to convey a sense of bumps and boundaries through varying the amount of tugging your finger feels on the touch surface. I am not sure when or if it can convey subtle or soft textures – however, there are so many ways to modulate the magnitude, shape, frequency, and repetition or the charge on the plate, that those types of subtle feedbacks may be possible in a production implementation.

I suspect a tight coupling between the visual and touch feedback is an important characteristic for the user to accept the touch feedback from the system. If the touch signal precedes or lags the visual cue, it is disconcerting and confusing. I was able to experience this on the prototype by using two fingers on the display at the same time. The sensing control algorithm only reports back a single touch point, so it would average the position between the two (or more) fingers. This is acceptable in the prototype as it was not a demonstration of a multi-touch system, but it did allow me to receive a feedback on my fingertips that did not match what my fingers were actually “touching” on the display.

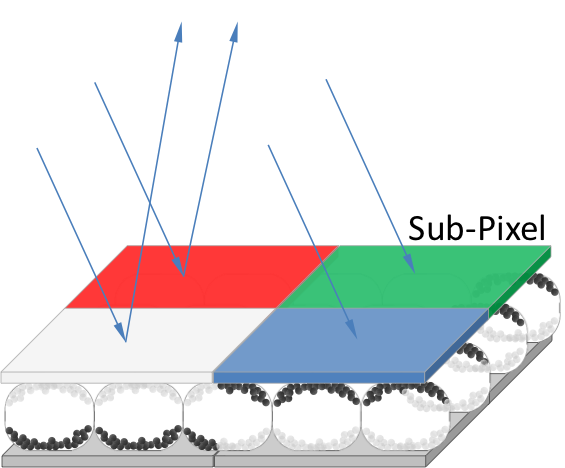

There is a good reason why the prototype did not support multi-touch. The feedback implementation applies a single charge across the entire touch surface. That means any and all fingers that are touching the display will (roughly) feel the same thing. This is more of an addressing problem; the system was using a single electrode. It might be possible in later generations to lay out different configurations so that the controller can drive different parts of the display with different signals. At this point, it is a similar constraint to what mechanical feedback systems contend with also. However, one advantage that the Tesla Touch approach has over the mechanical approach is that only the finger touching the display senses the feedback signal. In contrast, the mechanical approach relays the feedback not just to the user’s fingers, but also their other hand which is holding the device.

A final observation involves the impact of applying friction to our fingers in a context we are not used to doing. After playing with the prototype for quite some time, I felt a sensation in my fingertip that took up to an hour to fade away. I suspect my fingertip would feel similarly if I rubbed it on a rough surface for an extended time. I suspect with repeated use over time, my fingertip would develop a mini callous and the sensation would no longer occur.

This technology shows a lot of promise. It offers a feedback approach that includes no moving parts, but it may have a more constrained set of use-cases,versus other types of feedback, where it is able to provide useful feedback to the user.