There are many ways to use capacitive touch for user interfaces; one of the most visible ways is via a touch screen. An emerging use for capacitive touch in prototype devices is to sense the user’s finger on the backside or side of the device. Replacing mechanical buttons is another “low hanging fruit” for capacitive touch sensors. Depending on how the touch sensor is implemented, the application code may be responsible for working with low level sensing algorithms, or it may be able to take advantage of higher levels of abstraction when the touch use cases are well understood.

The Freescale TSSEVB provides a platform for developers to work with capacitive buttons placed in slider, rotary, and multiplexed configurations. (courtesyFreescale)

Freescale’s Xtrinsic TSS (touch sensing software) library and evaluation board provides an example platform for building touch sensing into a design using low- and mid-level routines. The evaluation board (shown in the figure) provides electrodes in a variety of configuration including multiplexed buttons, LED backlit buttons, different sized buttons, and buttons grouped together to form slider, rotary, and keypad configurations. The Xtrinsic TSS supports 8- and 32-bit processors (the S08 and Coldfire V1 processor families), and the evaluation board uses an 8-bit MC9S08LG32 processor for the application programming. The board includes a separate MC9S08JM60 communication processor that acts as a bridge between the application and the developer’s workstation. The evaluation board also includes an on-board display.

The TSS library supports up to 64 electrodes. The image of the evaluation board highlights some of the ways to configure electrodes to maximize functionality while using fewer electrodes. For example, the 12 button keypad uses 10 electrodes (numbered around the edge of the keypad) to detect the 12 different possible button positions. Using 10 electrodes allows the system to detect multiple simultaneous button presses. If you could guarantee that only one button would be pressed at a time, you could reduce the number of electrodes to 8 by eliminating the two small corner electrodes numbered 2 and 10 in the image. Further in the background of the image are four buttons with LEDs in the middle as well as a rotary and slider bar.

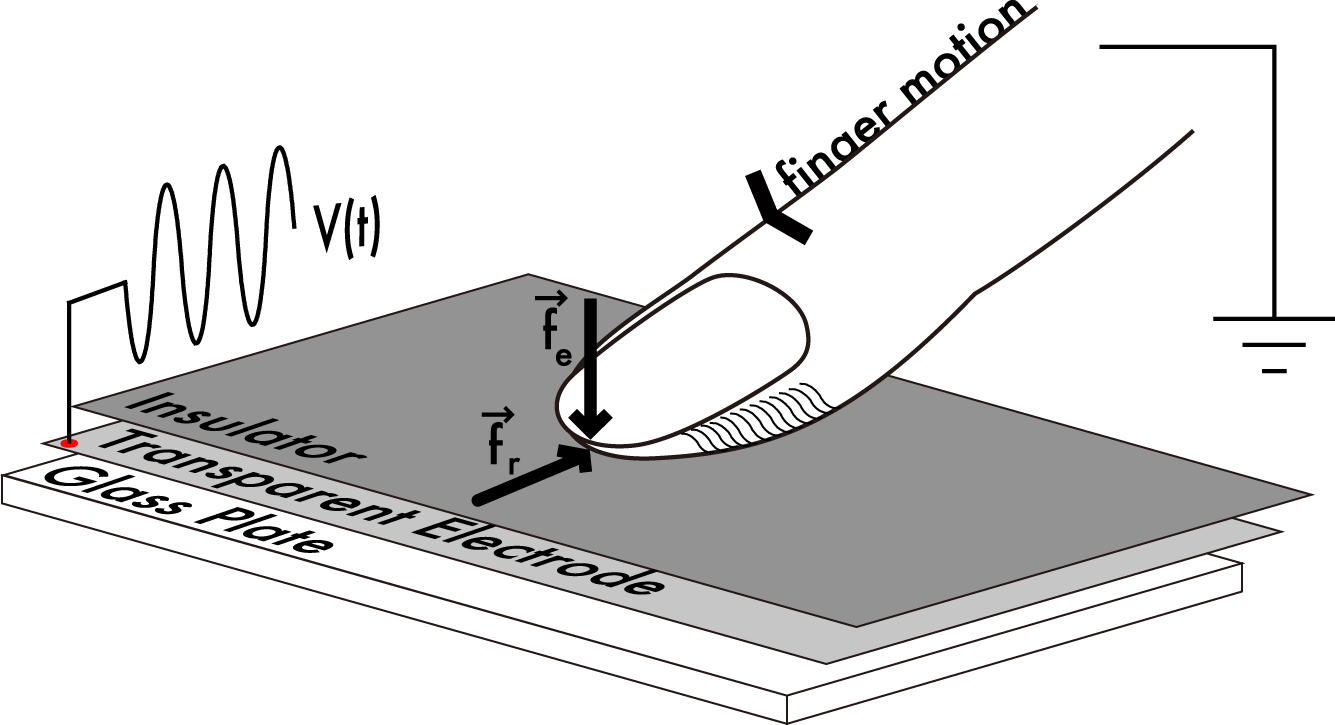

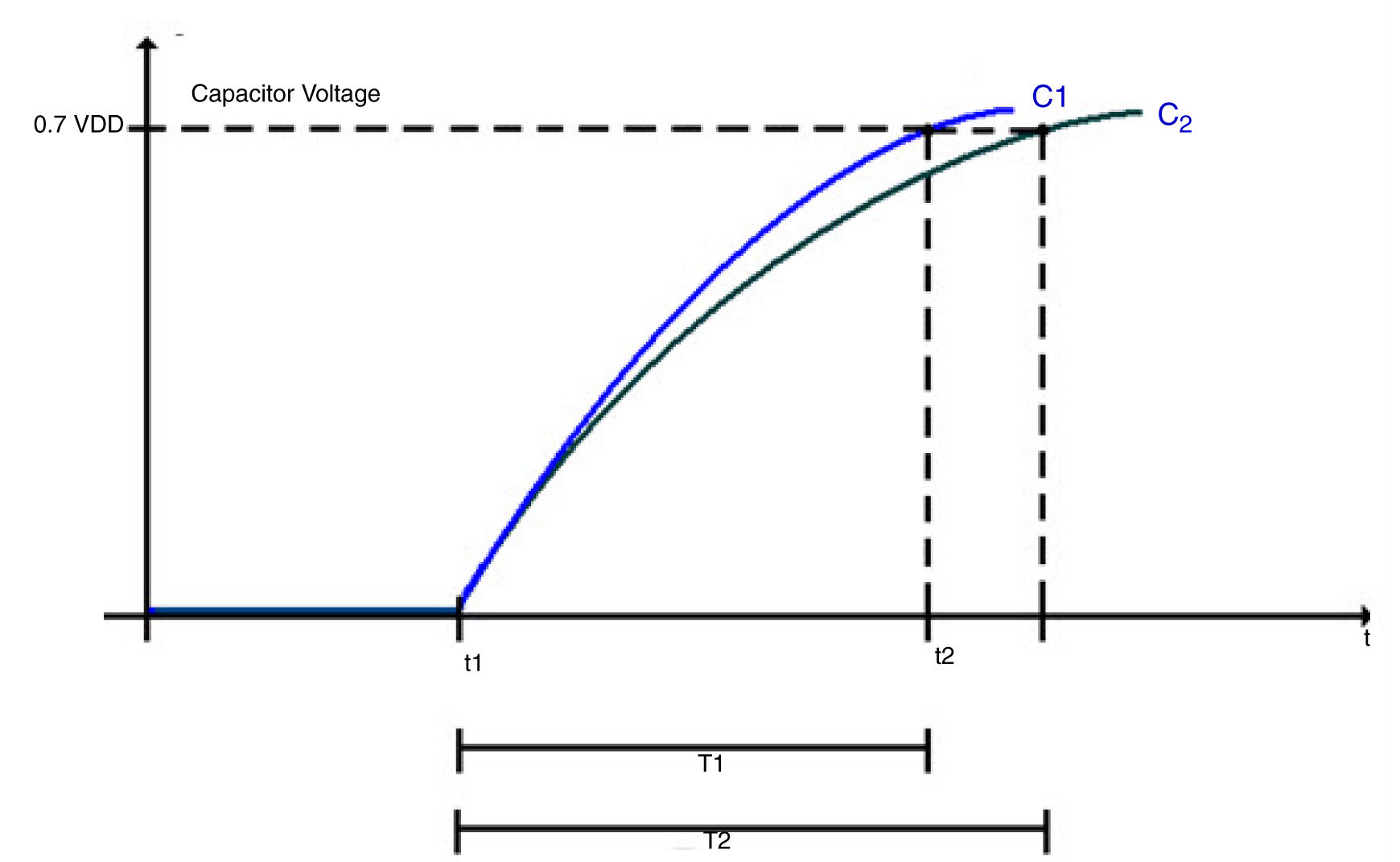

The charge time of the sensing electrode is extended by the additional capacitance of a finger touching the sensor area.

Each electrode in the touch sensing system acts like a capacitor with a charging time defined as T = RC. An external pull-up resistor limits the current to charge the electrode which in turn affects the charging time. Additionally, the presence or lack of a user’s finger near the electrode affects the capacitance of the electrode which also affects the charging time.

In the figure, C1 is the charging curve and T1 is the time to charge the electrode to VDD when there is no extra capacitance at the electrode (no finger present). C2 is the charging curve and T2 is the time to charge the electrode when there is extra capacitance at the electrode (finger present).The basic sensing algorithm relies on noting the time difference between T1 and T2 to determine if there is a touch or not.

The TSSEVB supports three different ways to control and measure the electrode: GPIO, the KBI or pin interrupts, and timer input capture. In each case, the electrode defaults to an output high state. To start measuring, the system sets the electrode pins output low to discharge the capacitor. By setting the electrode pin to a high impedance state, the capacitor will start charging. The different measurement implementations set and measure the electrode state slightly differently, but the algorithm is functionally the same.

The algorithm to detect a touch consists of 1) starting a hardware timer; 2) starting the electrode charging; 3) waiting for the electrode to charge (or a timeout to occur); and 4) returning the value of the timer. One difference between the different modes is whether the processor is looping (GPIO and timer input capture) or in a wait state (KBI or pin interrupt) which can affect whether you can perform any other tasks during the sensing.

There are three parameters which will affect the performance of the TSS library: the timer frequency, the pull-up resistor value, and the system power voltage. The timer frequency affects the minimum capacitance measurable. The system power voltage and pull-resistor affect the voltage trip point and how quickly the electrode charges. The library uses at least one hardware timer, so the system clock frequency affects the ability of the system to detect a touch because the frequency affects the minimum capacitance value detected per timer count.

The higher clock the frequency, the smaller the amount of capacitance the system can detect. If the clock rate is too fast for the charging time, the timer can overflow. If the clock rate is too slow, the system will be more susceptible to noise and have a harder time reliably detecting a touch. When I was first working with the TSSEVB, we chose less than optimally values and the touch sensing did not work very well. After figuring out there was a mismatch in the scaling value that we chose, the performance of the touch sensing drastically improved.

The library supports what Freescale calls Turbo Sensing, which is an alternative technique to measure charge time by counting bus ticks instead of using a timer. This increases the system integration flexibility and makes measurement faster with less noise and supports interrupt conversions. We did not have time to try out the turbo sensing method.

The decoder functions, such as for the keypad, slider, or rotary configurations, support a higher level of abstraction to the application code. For example, the keypad configuration relies on each button mapping to two electrodes charging at the same time. As an example, in the figure, the button numbered 5 requires electrodes 5 and 8 to charge together as each of those electrodes covers half of the 5 button. The rotary decoder handles more information than the key press decoder because it not only detects when electrode pads have been pressed, but it reports from what direction (of two possibilities) the pad was touched and how many pads experienced some displacement. This allows the application code to control the direction and speed of moving through a list. The slider decoder is similar to the rotary decoder except that the ends of the slider do not touch each other.

The size and shape of each electrode pad, as well as the parameters mentioned before, affects the charging time, so the delta in the T1 and T2 times will not necessarily be the same for each button. The charging time for each electrode pad might change as environmental conditions change. However, because detecting a touch is based on a relative difference in the charging time for each electrode, the system provides some resilience to environmental changes.